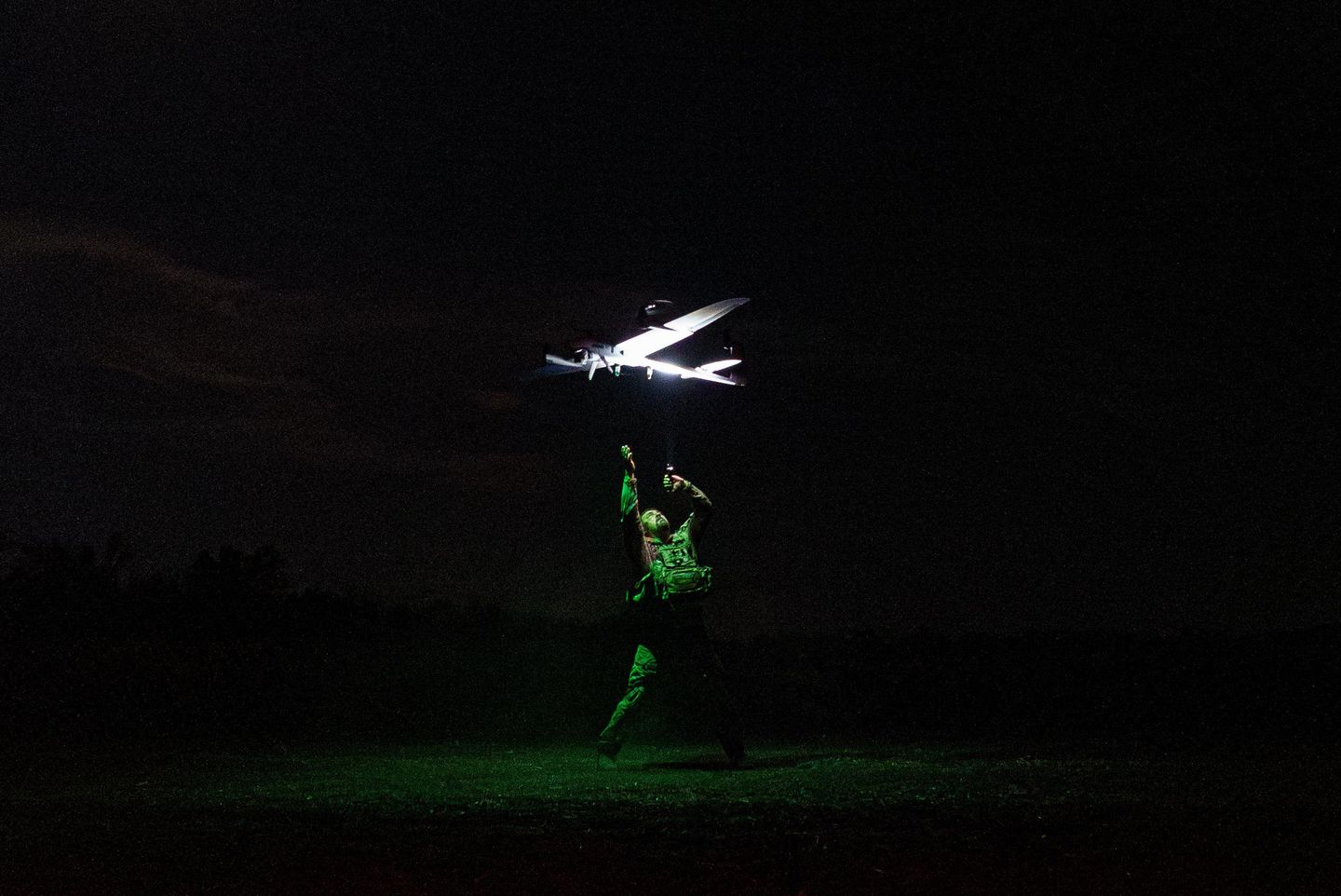

KYIV, Ukraine — The killer robots that have been staples of science fiction and Hollywood fantasy for decades are no longer imaginary — ruthlessly efficient AI-driven machines are meteing out death daily on the battlefields of Ukraine.

More than three years into Russia’s brutal invasion of its neighbor, the war raging on Ukraine’s eastern plains is increasingly being fought by machines.

Airborne drones constantly scan the broken landscape, shooting video. Computers use algorithms to sift through hours of footage in seconds. Battlefield software fuses sensor feeds into target lists. Semi-autonomous systems use those lists to help human operators steer drones carrying explosives through electronic jamming, smoke and adverse weather.

“It’s not about the future, it’s about the present”, says Iaroslav Honchar, co-founder of Aerorozvidka, a group of Ukrainian volunteers who have become experts on drone warfare while helping to defend the country.

“Artificial intelligence is already here, because the battlefield demands it,” Mr. Honchar says. “Sometimes we have more drones than operators, so we had to find ways to compensate.”

The unit, established in the wake of Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and the beginning of Moscow’s covert war in Donbas, has since pioneered many of Ukraine’s drone tactics.

“In the Donbas, necessity forced us to innovate,” Iaroslav Honchar says. “A mission that used to take 40 hours of analysis now takes seconds with AI.”

He credits automated classification tools trained to recognize tanks, trenches, roads or shorelines with driving tactical gains. But he warns of a downside: The more operators trust the machine, the more their own skills atrophy. Still, he calls the net effect “a revolution born of survival.”

From pilots to processors

The first revolution birthed by AI in this war wasn’t the introduction of death-dealing machines: It was the startling transformation of the speed at which war can be prosecuted. Ukrainian teams have moved computer-vision models from distant servers into the drones themselves, allowing them to keep identifying vehicles or trenches even when links are jammed.

“We train our models to recognize specific types of objects — tanks, trenches, roads, riverbanks — with 80 to 100% reliability depending on conditions,” Mr. Honchar says.

This onboarding of AI means that drones can process imagery, recognize vehicles or trenches and relay coordinates almost instantly without depending on vulnerable links to command posts.

Data from hundreds of UAVs are now fed into Ukraine’s Delta network, a real-time command platform fusing video, telemetry and coordinates. Within seconds, targets are automatically tagged, queued for verification and their coordinates relayed to artillery.

A report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies said that by letting onboard computers handle navigation and targeting, weaponized drones can dramatically multiply their accuracy.

However, those figures remain projections rather than battle-tested metrics.

Twist Robotics, the Kyiv-based makers of the Saker Scout reconnaissance drone, insist that AI must remain a copilot, not a commander. “Our system assists detection, classification, and navigation,” a representative told The Washington Times, “but it never fires automatically.”

Safeguards include geofencing and human validation. “Decisions to use force are never made autonomously.”

America’s slow revolution

While Ukrainian innovation is born of necessity, as the besieged country is faced with a numerically superior foe, the U.S. military’s own journey toward intelligent warfare has been slower and more cautious.

Retired Air Force Lt. Gen. John N.T. Shanahan, who led both Project Maven and the Joint AI Center, describes AI as a tool to “detect, classify, track — to augment, accelerate and automate pieces of the workflow, not to replace the analyst.”

“After eight years, we’ve made progress,” the general says, “but the Pentagon still spends too much on big hardware and not enough on code.”

The challenge now, he adds, is pushing AI “to the tactical edge,” so that machines can make sense of chaos in the field without crossing ethical lines.

“Autonomy doesn’t absolve responsibility,” he warns. “The judgment must remain human, but maybe it has to move upstream, to design, testing, and policy, if it can’t always happen at the trigger.”

Ukraine leveling-up its bureaucracy

One of Ukraine’s boldest innovations isn’t technological, but bureaucratic — and its concept sounds strikingly similar to a video game.

Ukraine offers bonuses for drone crews under a program called the “Army of Drones.”

Verified kills and destroyed equipment translate into points that Ukrainian units can then exchange for brand-new equipment.

Drone crews upload footage of their strikes to Delta, Ukraine’s military data network, where an AI-assisted verification team from the Defense Ministry and Brave1 reviews each hit before awarding points.

Meanwhile, the state-run Brave1 Market platform has streamlined the procurement process.

Through it, brigades can directly exchange their points for drones, ground robots or electronic warfare systems, bypassing red tape.

“Before, contracts took months,” says Andrii Hrytseniuk, head of Brave1. “Now it takes around two weeks. It’s revolutionary, even by NATO standards.”

According to Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation Mykhailo Fedorov, in September alone, Ukrainian drone units reported over 18,000 verified Russian personnel struck, double the total recorded a year earlier.

“As of October 2025, 130 brigades had access to the platform, according to official announcements.

“The incentive works,” Mr. Hrytseniuk says. “Changing the reward for a target can shift behavior faster than any order from headquarters. It’s transparent competition, not chaos.”

That sentiment was echoed by Oksana Rubanyak in a recent interview with Ukrainian media “Newsroom,” the drone company commander said that the point system “creates additional internal psychological motivation for the team in the form of a healthy competitive spirit.”

Warfare enters the console age

The first public scoring table, released by United24 Media in May 2025, offered six points per neutralized enemy soldier, 20 for a damaged tank, 40 for a destroyed one, and up to 50 for a rocket launcher.

But by autumn, Kyiv had doubled the value for personnel targets as Russian forces adapted their tactics and shifted toward probing attacks conducted by smaller groups of infantrymen.

The point system has since expanded. Points can now be earned for mapping enemy positions, neutralizing electronic warfare systems, or even by substituting unmanned ground vehicles for soldiers to conduct logistics missions.

“We want machines, not people, taking the risks,” Mr. Hrytseniuk says.

For soldiers, the incentive is obvious: better performance is rewarded with access to better, more modern equipment. For outsiders, however, the optics can be unsettling, as the act of killing and destroying increasingly resembles a video game.

The rules of the game

Chad Bird and Michelle Lukomski, legal scholars at West Point’s Lieber Institute for Law & Warfare see both promise and peril in Ukraine’s experiment.

In their June 2025 paper titled “Ready Soldier One: Video Game Incentives and Law of Armed Conflict Compliance,” they argue that while such reward systems can reinforce discipline, as each strike must be documented and verified, they also risk desensitizing operators or skewing priorities if scores overshadow restraint.

“The system must complement, not replace, command oversight and legal review,” they write.

A Ukrainian soldier who wished to remain anonymous shared similar concerns with The Washington Times: “I’ve heard that the points system, due to its emphasis on damage to equipment and the lower value of infantry, influences the tactics used with our drones.”

However, he notes that the Russians’ overwhelming numerical superiority tends to undermine those concerns. “We strike everything we can, and there aren’t so many targets that our crews are forced in mid-flight to choose between equipment and infantry.”

Last human in the loop

Klaudia Klonowska, a legal expert at The Hague’s Asser Institute, shares the concern. The once-favored phrase “meaningful human control,” she says, has given way to “sufficient human judgment.”

In the field, she explains, a remotely piloted drone can slip into autonomy when the signal is jammed, and legal categories like “in the loop” or “out of the loop” collapse.

“The reality of combat doesn’t fit our old frameworks,” she tells The Times. “Software evolves daily, sometimes faster than the lawyers can review it.”

Despite the growing preponderance of algorithms, humans still anchor the process. Twist Robotics enforces human validation for every potentially lethal engagement. Mr. Hrytseniuk meanwhile insists the system “does not make war any easier, it makes it fairer and faster.”

Mr. Honchar is more direct. “When a Shahed [an Iranian-made drone used by Russian forces] heads toward your city, the moral question is how to stop it in time.”

Mr. Shanahan, watching from Washington, calls Ukraine’s battlefield “a laboratory for the next decade.”

The race, he says, “isn’t for killer robots, it’s for tempo. Whoever iterates faster wins.”

Half a century after the fictional mechanized armies of “Terminator” “Blade Runner” waged war on humanity, the central question posed by those films — what separates human from machine? — now seems less rhetorical and more urgent.